Effects and Damages of Hail Storms

What are the effects of hail on residential roofing products?

This article examines the sometimes-devastating effects that hail can have on asphalt shingles, wood shingles and shakes, and concrete tile shingles

by Jim D. KoontzRoofing products are subject to a number of severe weather exposures. These exposures include ultraviolet radiation,

heat, wind, rain, pollutants and hail. Hail damage to roofing products results in millions of dollars of losses on

an annual basis. The result of this damage is an obvious boon for roofing contractors and, over the years, has certainly

been very costly for the insurance industry. The ultimate cost, however, is borne by consumers.

Hail damage can affect virtually all types of roofing systems, including both commercial and residential. For the

purposes of this paper, however, the primary area to be examined will be the hail resistance of common residential

roofing products: asphalt shingles, wood shingles and shakes, and concrete tile shingles.

Whenever a city in North America is subjected to a severe hail storm, and the dollar losses exceed $5 million, the

area is listed as a catastrophic loss area by the American Insurance Association. This is a methodology in which

the insurance industry can then keep statistics on the amount of loss for each particular geographical location.

These numbers are later used in actuarial tables to develop insurance rates for any given location.

In the United States, the geographical frequency of hail has been studied by groups such as the National Board of

Catastrophe (from 1949 to 1964) and the United States Weather Bureau (from 1950 to 1960). The data from both groups

indicate that a large number of severe hailstorms tends to occur in the central section of the United States. This

covers an area from South Texas to Minnesota and from Colorado to Illinois. It should be pointed out, however, that

no area in North America is totally excluded from the possibility of a hail storm occurrence.

The hail phenomena

Research on the phenomena of hail has been performed throughout the world, with the bulk being performed in Europe, South

Africa, Australia and North America. Hail varies by size, shape, density and terminal velocity.

Three of these factors size, density and terminal velocity affect the overall impact energy of hail.

1. Size: The size of hail has been reported from as small as sleet ( inch or 6.35 mm) to sizes reportedly larger

than softballs, with diameters exceeding 5 inches (127 mm). The frequency of hail and the number of impacts for any

given area also varies. The overriding factor, however, of whether a hailstorm can inflict damage to a roofing system

is the ultimate impact energy, or kinetic energy, imparted by the hailstone to the roofing system, and the impact

resistance of the roofing system.

1. Size: The size of hail has been reported from as small as sleet ( inch or 6.35 mm) to sizes reportedly larger

than softballs, with diameters exceeding 5 inches (127 mm). The frequency of hail and the number of impacts for any

given area also varies. The overriding factor, however, of whether a hailstorm can inflict damage to a roofing system

is the ultimate impact energy, or kinetic energy, imparted by the hailstone to the roofing system, and the impact

resistance of the roofing system.

2. Shape: The shape of hail can be spherical or somewhat elliptical. For purposes of this particular study, spherical

hailstones were used.

3. Density: Studies have shown that hailstones vary in density. In cold-weather storms, relatively soft hail with

small diameters is generated. In the warmer, spring- type weather, however, large hail (several inches in diameter)

is generated with a relatively high density.

Hail is initially formed as an embryonic droplet that goes through a series of updraft cycles. Each cycle of rising

and falling adds a layer of ice to the hailstone. The stronger the updraft force, the higher the hail is carried

to colder and colder regions of the atmosphere. At these colder regions, the density of hail will increase, and approach

that of ice (about 0.9 grams per cubic centimeter). Measurements of soft hail will show densities ranging from 0.5

to 0.7 grams per cubic centimeter.

It is normally assumed that hail has a density that approximates that of ice. However, a number of researchers have

pointed out that hail is somewhat layered, and often consists of rings of ice. For purposes of this study, an overall

density of 0.9 grams per cubic centimeter was used.

4. Terminal velocity: The terminal velocity of hailstones was originally determined by J.A.P. Lauri. These terminal

velocities (see Figure 1) have been used throughout the industry in other research, particularly that performed by

the National Institute of Standards and Technology (formerly the National Bureau of Standards).

Terminal velocity assumes that a hailstone free-falls straight down, or in a vertical direction. However, it has

generally been observed in severe hailstorms that hail does not fall vertically, but impacts surfaces at an angle.

Obviously, the terminal velocity of the hailstone is determined by its free-fall velocity and its component horizontal

wind velocity. An example would be a 2-inch (51-mm) hailstone that would have a free-falling terminal velocity of

105 feet per second (32 meters per second) or 72 mph. If this stone was associated with a 59-feet per second (54

meters per second) or 40-mph horizontal wind, the resultant terminal velocity would increase to 120 feet per second

(36 meters per second) or 82 mph.

Terminal velocity assumes that a hailstone free-falls straight down, or in a vertical direction. However, it has

generally been observed in severe hailstorms that hail does not fall vertically, but impacts surfaces at an angle.

Obviously, the terminal velocity of the hailstone is determined by its free-fall velocity and its component horizontal

wind velocity. An example would be a 2-inch (51-mm) hailstone that would have a free-falling terminal velocity of

105 feet per second (32 meters per second) or 72 mph. If this stone was associated with a 59-feet per second (54

meters per second) or 40-mph horizontal wind, the resultant terminal velocity would increase to 120 feet per second

(36 meters per second) or 82 mph.

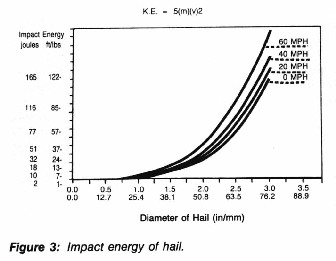

The overall increase in kinetic energy would be from 23.29 pound force (31.58 joules) to 30.24 pound force (41.0

joules), or an increase of 30 percent in impact energy. By varying the horizontal wind factor, the ultimate impact

energy can be varied dramatically (see Figure 2). In reviewing this initial data, it is also interesting to note

the overall difference in impact energy between hailstones with diameters of I inch (25.4 mm) and 2 inches (51 mm).

Increasing the diameter of the hail from I inch to 2 inches increases the ultimate impact energy from less than I

foot per pound (1.4 joules) to approximately 22 foot per pound (29.83 joules see Figure 3). The approximate impact

energy obviously increases on an exponential scale, which is determined by the mass and the increase in terminal

velocity. These two factors, mass and velocity (which are both increasing exponentially), cause a dramatic increase

in the impact energy with small, incremental fluctuations of hail diameters.

Testing equipment that was used

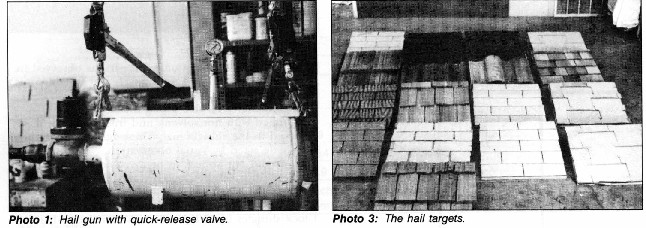

To test various residential roofing products for resistance to hail damage, a hail gun was constructed.

This gun consisted of a pressurized air tank fitted with a quick-release, electronically actuated valve (see Photo1).

The barrels of the hail gun were interchangeable to accommodate the size of the hail, which was formed in molds (see

Photo 2).

By pressurizing the tank and by opening the electronically actuated, quick-release valve, the sudden surge of air

pressure propels the hailstone towards the target. To accurately measure the terminal velocity of the hailstone,

a ballistic timer was used. Once this equipment was assembled, the hail gun was calibrated between air pressures

and terminal free-fall velocities for different sizes of hailstones.

Hailstone targets that were used

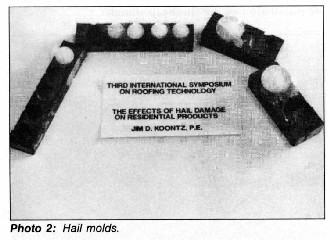

Nineteen roofing assemblies were tested for resistance to hail damage (see Photo 3). The substrate of 18 of the

samples was '/2 inch (12.7-mm) CDX plywood. One sample was tested with 1/2 inch (12.7-mm) OSB decking. Prior studies

have shown that variations in the substrate can affect the puncture resistance of roofing assemblies. All targets

were constructed on 2-foot x 2- foot x '/2 -inch (.61-mm x .61-mm x 12.7-mm) sheets. And all were constructed with

one layer of ASTM D226-Type-l organic underlayment beneath the shingles. Eleven of the targets were asphalt shingles

with either fiberglass or organic mats, in a three-tab, T-lock, grain pattern and layered, and simulated wood configuration.

Three wood shingle targets had medium shake shingles, cedar shingles and 20-year-old, heavy red cedar shake shingles.

Three concrete tiles were used in three configurations: "S," barrel and shake.

Nineteen roofing assemblies were tested for resistance to hail damage (see Photo 3). The substrate of 18 of the

samples was '/2 inch (12.7-mm) CDX plywood. One sample was tested with 1/2 inch (12.7-mm) OSB decking. Prior studies

have shown that variations in the substrate can affect the puncture resistance of roofing assemblies. All targets

were constructed on 2-foot x 2- foot x '/2 -inch (.61-mm x .61-mm x 12.7-mm) sheets. And all were constructed with

one layer of ASTM D226-Type-l organic underlayment beneath the shingles. Eleven of the targets were asphalt shingles

with either fiberglass or organic mats, in a three-tab, T-lock, grain pattern and layered, and simulated wood configuration.

Three wood shingle targets had medium shake shingles, cedar shingles and 20-year-old, heavy red cedar shake shingles.

Three concrete tiles were used in three configurations: "S," barrel and shake.

Two of the previously impacted asphalt shingle targets (constructed of 15-year-old, three-tab organic and T-lock

organic) were then overlaid with new shingles (three-tab fiberglass and T-lock fiberglass, respectively). These roofing

assemblies were included in the study because, in many cases, hail-damaged residential roofs are simply overlaid

with a second layer of shingles. The older shingles, by default, serve as an underlayment on many residential roofing

projects. Most building codes, however, do not allow a third layer due to potential structural limitations. It has

also been experienced that the fastener length for a third layer of shingles becomes too long and results in some

movement of the roofing materials due to a slight

flexing, or rotation, of the fastener itself.

Testing procedures

Each sample was impacted by hail 15 times. This included five different sizes of hail % inch (19 mm), I% inch (32

mm), I % inch (44 mm), 2 inch (51 mm) and 21/2 inch (64 mm impacting at three different angles of impact (15, 45

and 90 degrees see Figure 4). A variation in the angle of impact from 15, 45 to 90 degrees produces a resultant force

ranging from 25.88 percent, 70.7 percent and 100 percent, respectively. Simulated hailstones were frozen in molds

at approximately 10 F (12 C). The hailstones were quickly removed, placed in the gun barrel and fired within 30 seconds

of loading. Following the impact of each specimen, results were recorded. Tests were performed at a room temperature

of about 80 F (27 C).

Each sample was impacted by hail 15 times. This included five different sizes of hail % inch (19 mm), I% inch (32

mm), I % inch (44 mm), 2 inch (51 mm) and 21/2 inch (64 mm impacting at three different angles of impact (15, 45

and 90 degrees see Figure 4). A variation in the angle of impact from 15, 45 to 90 degrees produces a resultant force

ranging from 25.88 percent, 70.7 percent and 100 percent, respectively. Simulated hailstones were frozen in molds

at approximately 10 F (12 C). The hailstones were quickly removed, placed in the gun barrel and fired within 30 seconds

of loading. Following the impact of each specimen, results were recorded. Tests were performed at a room temperature

of about 80 F (27 C).

All hail was fired at its terminal free-fall velocity (Figure 1). Concrete tile targets were then impacted in a

secondary test with hail at speeds higher than normal terminal velocity to simulate the effects of high horizontal

winds, A fiberglass three-tab assembly over a plywood deck was subjected to three surface temperatures 60 F(15.6

C), 80 F (27 C) and 120 F (49 C) for hail damage evaluation with a 2-inch (51-mm) hailstone. The effects of higher

and lower surface temperatures were then evaluated.

Damage assessment

Evaluating marginal damage to roofing products has not been clearly understood by either the roofing or insurance industries. Catastrophic failure damage is very clear and easy to observe. This would be a complete fracture/puncture through the installed residential roofing product. Other types of damage, however, are not so obvious. Indentations may not fracture, but may result in some aesthetic loss, or in some potential loss of performance in years to come. As each of the targets was impacted with hail, the visible damage was recorded in a table (see Figure 5 for a representative number of testing samples). Various ratings for damage were used: ND (No Damage); I (Indentation); IG (Indentation with Granule Loss); ED (Edge Damage); IF (Indentation with Fracture); and P (Puncture). In some cases, an indentation can occur, and the fracture in either the reinforcement mat (fiberglass or organic) or in some cases, even a fracture in the wood shingle is not readily observable. In the case of an organic or fiberglass mat shingle, desaturation of the shingle may be required to observe the damage. In the case of a wood shingle, close examination may be required to observe the split or fracture.

Asphalt shingle performance

Fourteen assemblies of asphalt shingles were targeted.

Damage varied from no damage to puncture. All of the new, single-layer, fiberglass three-tab shingle assemblies

had a resistance to fracture in the % -inch (19-mm) to I %-inch (64-mm) category, with an angle of impact ranging

from 15 to 90 degrees. Fiberglass asphaltic shingles installed over OSB decking had the same degree of fracture resistance

as similar shingles installed over plywood decking.

Damage varied from no damage to puncture. All of the new, single-layer, fiberglass three-tab shingle assemblies

had a resistance to fracture in the % -inch (19-mm) to I %-inch (64-mm) category, with an angle of impact ranging

from 15 to 90 degrees. Fiberglass asphaltic shingles installed over OSB decking had the same degree of fracture resistance

as similar shingles installed over plywood decking.

Indentations in the bulk of these areas were superficial, with just minor granule loss. It was observed in some

shingles, such as Target No. I, that indentations would occur (hail size of 2 inches or 51 mm, 90-degree angle).

At this point, the shingles were desaturated with hot solvent, and fractures were observed in the shingle mat. These

fractures were not readily detected by visual observation.

There did not appear to be a visible difference in hail resistance between organic and fiberglass threetab products.

The three-tab, assembly-type shingles, however, did have a higher hailstone resistance than T- lock shingles (see

Photo 4). This increase in hail resistance appears to be a result of the smoother, flatter installation of the three-tab

shingles. The heavier-weight, laminated shingles (Target No. 7) offered a slightly higher hail resistance to that

of other fiberglass shingles in that a fracture did not occur until 2-inch hail (51-mm) at a 90-degree angle impacted

the target. It should be pointed out, however, that the damage was not readily visible, and could not be observed

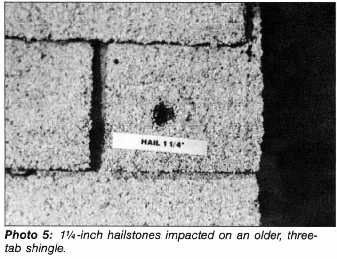

until the shingle was desaturated. The older, organic three-tab and T-lock shingles exhibited a very low threshold

of hail resistance (see Photo 5). As shingles age, asphalt within the shingle obviously hardens and becomes somewhat

more brittle. This creates a situation in which tow residences could be next door to one another, and one residence

could sustain damage to a slightly older roof, while the other residence could have virtually no damage with a new

roofing system. When a roof system is overlayed, there is an increased void space between the new and old shingles.

This is particularly evident in the case of new T-locks installed over old T-locks, In this situation, as demonstrated

by Target No. 13, a fracture occurred with hail as small as I ~ inches (32 mm) fired at a 90-degree angle. All

asphalt shingles had a fairly low threshold of damage when the impact occurred at the butt edge (or shingle cutout)

in a three-tab assembly. This typically produces a somewhat semi-circular break at the leading butt edge. Although

this may not effect the performance of the shingle, it may cause some slight problems from an aesthetic standpoint.

Variations in temperature

Temperature of the roof assembly surface is a definite factor in hail damage (see Target No. 14), Lower surface temperatures, such as 60 F (15.6 C), are much more prone to fracture than higher surface temperatures. This produces a lower threshold for damage. The asphalt into which the granules are imbedded appears to shatter more readily at colder temperatures. When the surface temperature of the shingle is somewhat higher, such as 120 F (49 C), the surface is somewhat softer and, though easily indented, does not readily fracture.

Wood, Saw Cut, One Side

Wood, Saw Cut, One Side

24 inches long

10-inch exposure

112 inches thick

Wood shingle performance

Three different groups of wood shingles were used; new No. I red cedar shingles, new No. I red cedar handsplit mediums and 20-year-old No. I red handsplit heavies.

Three different groups of wood shingles were used; new No. I red cedar shingles, new No. I red cedar handsplit mediums and 20-year-old No. I red handsplit heavies.

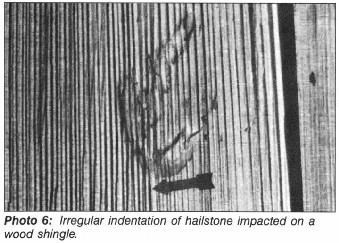

The three wood shingles that were tested exhibited various degrees of indentation, which occurred at very low thresholds of kinetic energy. When the wood shingles were impacted with hailstones from "A inches (19 mm) in diameter to I % inches (44 mm) in diameter, fairly uniform indentions occurred. The indentations,

depending upon the angle of impact, were either circular or somewhat elliptical. Damage in this particular area,

for the most part, was superficial, and would not effect the overall performance of the roofing system, When the

wood shingles (Targets No. 15 and 16) were impacted with hailstones I % inches (44 mm) or larger, the shape of the

indentation was not uniform (see Photo 6). This was due to two factors: One, the hail tends to crush and rotate somewhat

as it impacts the shingle; two, because the surface of the wood shingle is irregular, the indentation becomes erratic.

The threshold for damage within the wood shingle was not clear-cut.  This can obviously be due to the different thicknesses of the wood, points of impact, and non-uniform surfaces and

sub-surfaces. An example is the '/2 inch (13-mm) No. I red cedar handsplit medium shingle, where, at a 90-degree

angle of impact, splits developed in the shingles with hailstones of I Vf inches (32 mm) and I % inches (44 mm).

Indentations occurred, however, with 2-inch (51-mm) hail followed by fractures with 214 -inch (64-mm) hail. The thicker

wood shingles did not necessarily result in higher hailstone resistance. The thinner red cedar shingles (% inch or

9.5 mm) with smoother surfaces and a greater uniformity in the substrate produced hailstone resistance equal to the

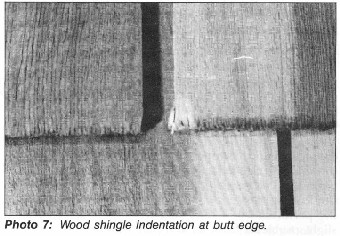

thicker shingles. Some indentation of the wood shingles did occur at the leading butt edge and at the joint of the

shingles. The bulk of this damage is somewhat superficial, and began at a fairly low threshold of kinetic energy

(see Photo 7).

This can obviously be due to the different thicknesses of the wood, points of impact, and non-uniform surfaces and

sub-surfaces. An example is the '/2 inch (13-mm) No. I red cedar handsplit medium shingle, where, at a 90-degree

angle of impact, splits developed in the shingles with hailstones of I Vf inches (32 mm) and I % inches (44 mm).

Indentations occurred, however, with 2-inch (51-mm) hail followed by fractures with 214 -inch (64-mm) hail. The thicker

wood shingles did not necessarily result in higher hailstone resistance. The thinner red cedar shingles (% inch or

9.5 mm) with smoother surfaces and a greater uniformity in the substrate produced hailstone resistance equal to the

thicker shingles. Some indentation of the wood shingles did occur at the leading butt edge and at the joint of the

shingles. The bulk of this damage is somewhat superficial, and began at a fairly low threshold of kinetic energy

(see Photo 7).

Concrete tile shingle performance

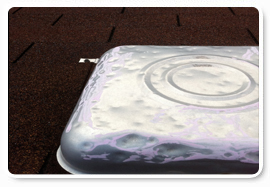

The three concrete tile targets all exhibited fairly high degrees of hail resistance.Fracture/breakage did not occur

with the 2 '/a -inch (64-mm) hail at a 90-degree angle of impact. Fracture/breakage did occur, however, when the

velocity was increased to 131 feet per second (40 meters per second) or 89 mph, resulting in kinetic energy of 71.49

feet per second (96.9 joules see Photo 8). The flatter concrete tile shingle was the most hailresistant concrete

tile product tested. Multiple impacts with 2%-inchhh (64-mm) hail was required before fracture/breakage occurred.

The three concrete tile targets all exhibited fairly high degrees of hail resistance.Fracture/breakage did not occur

with the 2 '/a -inch (64-mm) hail at a 90-degree angle of impact. Fracture/breakage did occur, however, when the

velocity was increased to 131 feet per second (40 meters per second) or 89 mph, resulting in kinetic energy of 71.49

feet per second (96.9 joules see Photo 8). The flatter concrete tile shingle was the most hailresistant concrete

tile product tested. Multiple impacts with 2%-inchhh (64-mm) hail was required before fracture/breakage occurred.

In conclusion

Damage to residential roofing products is an obvious result of the size of hail, angle of impact, age of materials, type of roofing system, temperature and substrate condition. If the angle of impact is great enough, a situation could occur in which one side of a sloped residential roof is severely damaged due to an impact with a high Fiberglass and organic three-tab materials, in singlelayer applications over either plywood or OSB deck ing, appear to offer a high degree of hail resistance in asphaltic shingle construction. It is obvious that in some questionable circumstances, desaturation of asphalt shingles is required to determine whether or not the reinforcing mat has suffered damage. Threshold damage of wood shingle roofs are a result of the point of impact on the shingle assembly. Fracture of the wood shingles appears to be somewhat dependent upon whether the shingles are sawn on one or both sides. When the shingles lay relatively flat, as in a doublesawn shingle, resistance to hail damage appears to improve. Concrete tile systems appear to offer a very high degree of hail resistance. The lower-profile shingle either flat or lower configurations result in increased hail resistance. normal resultant force, while the opposite side may have minimal to no damage because a glancing type of impact may have occurred.

Jim Koontz, PE, is president of Jim Koontz & Associates Inc.,

Hobbs, New Mexico. For a copy of references and the

complete testing results (Figure 5), contact NRCA's Aimee

Anderson at (708) 299-9070.

Illinois Hail Damage & Storm Damage

Every year storms tear through the Lake County area leaving neighborhoods devastated. If a severe storm hits your home, do you know what to look for? How do you know if your home is truly damaged?

As "Storm Damage Claim Specialists", we specialize in the replacement of Roofing, Siding, Windows, Gutters, Painting, Drywall and more. Our Illinois siding company provides a variety of siding options including vinyl siding, steel siding, siding repair and replacement, cedar siding, and a variety of other siding solutions. Our Lake County Roofing Contractors are trained specialists and you can set an appointment with us at a time that is convenient for you for an estimate on your needs.

Whether you just made it through a hail storm, wind storm, or tornado, you will want to contact your insurance company immediately.

Next, call KMK Residential Restorations Inc. Roofing & Siding. so that we can get a specialist to promptly and thoroughly inspect your home.

Our estimators are well trained and will work on your behalf with your insurance company. Having one of our specialists present upon your insurance company's inspection can be very beneficial when identifying project work. Our specialist will explain the claim process from start to finish to ensure any decisions that need to made by the homeowner are well informed decisions.

You can rest assured that our specialist will meet your insurance company's adjuster at your property to perform a thorough inspection. We will make sure all items are accounted for and we use the same industry standard computer software that your insurance company uses to ensure that the proper settlement is reached.

We offer 24/7 emergency tarping services during and after any major storms.

Illinois Roofing Contractors & Replacement

Wind damage tends to be pretty obvious. Generally a homeowner will see missing shingles, siding, loose gutters, etc. However, just because the damage isn't obvious, don't rule out damage that be hidden such as loose or broken items.

Hail damage varies. It can be as obvious as huge welts on shingles, holes or dents to siding, or even broken window panes. Nevertheless, be sure to have one of our specialists do a thorough inspection of your property. The exterior of your home could have hail damage without you even realizing it. Smaller hail damage is hard to find and often times requires a trained eye.

Water damage tends to be fairly obvious. A home owner will see wet drywall and/or sheetrock as well as standing water or saturated flooring materials. If water is penetrating your home, be sure to give us a call so that we can assist you with any emergency repairs to keep the situation from getting worse.

Here are links to the most widely used insurance companies:

If your insurance company is not on this list, contact your agent or do an online search!

© Copyright 2019

© Copyright 2019